I was born and raised along with my twin brother (Terry, ’78) in Springfield, Ohio 45 miles from Columbus. So, it raised a few eyebrows when we skipped attending the local state school and both enrolled at the University of Michigan on ROTC scholarships (Terry, Navy and myself, Army) to pursue engineering degrees in the fall 1974. I enjoyed living in Mosher-Jordan Hall because it was close to the engineering classrooms at the time (East & West Engineering), athletic facilities at the old North Gym and the ROTC building, but it was dorm life.

I was born and raised along with my twin brother (Terry, ’78) in Springfield, Ohio 45 miles from Columbus. So, it raised a few eyebrows when we skipped attending the local state school and both enrolled at the University of Michigan on ROTC scholarships (Terry, Navy and myself, Army) to pursue engineering degrees in the fall 1974. I enjoyed living in Mosher-Jordan Hall because it was close to the engineering classrooms at the time (East & West Engineering), athletic facilities at the old North Gym and the ROTC building, but it was dorm life.

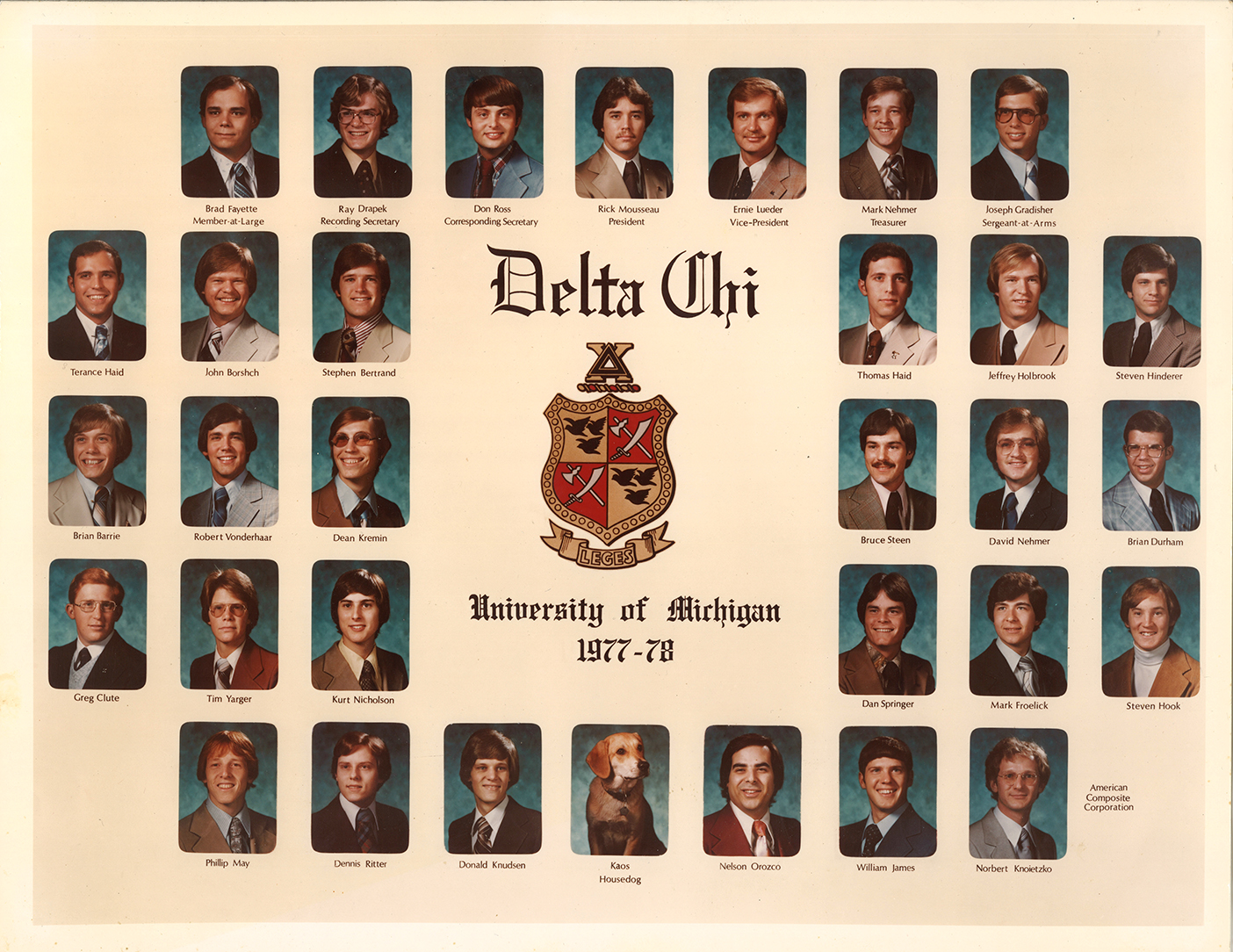

Terry had pledged Delta Chi during fall rush ’74, and I followed suit in the spring, learning the history and rituals of the fraternity with the help of my Big Brother, Robert Nidzgorski ’75. After earning my Army parachute wings at Ft. Benning, GA after my freshman year and enjoying the last summer I would spend at home in Ohio, I moved into the house for the start of my sophomore year. I ended up living in the house for 3 years, first enjoying the amenities of Front Triple (above cook John Henry Russell) with Terry and wild man Lane Bertrand ’78, then the Fireside double, and finally a single on the top floor across from Mr. Mellow, Ernie Lueder ‘78.

The fraternity was more than a house, with great cooking (thanks to JR) for me. I was on scholarship with monthly military training exercise obligations and was also fortunate to be a Varsity Cheerleader (junior year), work at the Village Bell (senior year) and be part of Michigamua (senior year). Delta Chi was a tribe – a group to experience life with, outside the rigors of the engineering classes and the ROTC drills. I’ll always remember serenading a sorority (hats off to the Glee Club members who carried the rest of us); getting our ass kicked in flag football in spite of the playmaking of Ron Scafe ’77 and Scott Kellman ’78; Scott Leak ’77 stumbling downstairs to the basement for his morning bottle of Coke; or Lane, Norm Anschuetz ’78 and Brian Barrie ’78 streaking in the middle of Hill St. In a nutshell, I had brothers who were different from me – and that was good.

I graduated in April 1978 on a Saturday with a bachelor’s degree in Naval Architecture & Marine Engineering. 48 hours later I reported to Ft. Bragg, NC as a newly minted 2nd Lieutenant, assigned to the 27th Engineer Battalion (Combat) (Airborne). My intent was to complete my 4-year commitment and then return to life as a citizen. As a platoon leader in a premier combat unit, I was given a lot of training opportunities and became a parachute instructor, along the way earning the U.S. Army Ranger tab, Pathfinder badge (the team that parachutes in early to set up the drop zone for the main body) and the Master Parachute badge.

Two things stand out from my time at Ft. Bragg. It was a period of transition for the U.S. Army, from a focus on the cold war and defending the Fulda Gap in Germany, to addressing emerging threats including the Middle East. In the 1960’s, the military had developed a man-portable nuclear device (the Small Atomic Demolition Munition or SADM). As part of the old threat, I was trained to parachute into Soviet-occupied western Europe with the SADM and destroy power plants, bridges, and dams. It was considered a one-way trip; while the device had a timer, none of us figured we could plant the device, evade detection, and get clear before the device went off.

The second thing involved the 1st Special Forces Operational Detachment-Delta (SFOD-D), commonly referred to as Delta Force. Delta Force was established 6

Instead of getting out when I could, I ended up spending 20 years on active duty, essentially rotating between Infantry Divisions and Engineer assignments. After Ft. Bragg I commanded Bravo Company, 2nd Engineer Battalion, 2nd Infantry Division for 18 months, the combat engineer company assigned to the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) separating North & South Korea. The DMZ was active then, with nightly gun battles across the border and regular attempts to insert commandos behind our lines. Tensions increased after the October 1983 failed assassination attempt (in Rangoon, Burma) against the president of South Korea and I slept with my pistol under my pillow for the remainder of my command. Following Korea, the Army allowed me to be a student for 18 months and I graduated from U.C. Berkeley in 1985 with a Master of Engineering (ME), Civil Engineering degree.months before I arrived at Ft. Bragg; you may remember they were part of the failed mission in April 1980 to rescue U.S. hostages held in Iran. Many lessons came from the failure, including the need to have a reliable airstrip closer to Iran, to reduce the travel needed by helicopter. The Russians had built a military-grade runway in a remote section of northern Somalia, before getting kicked out in the late ‘70’s when they switched their regional support to Ethiopia. With literally nothing but a long patch of concrete, it needed a little upgrade to make the U.S. Air Force happy. In 1981, I was part of a small team that discretely deployed for a month and installed guidance equipment and runway lights that could be activated remotely from the air.

|

Except for a tour as the Executive Officer, 82nd Engineer Battalion, 3rd Infantry Division (Mechanized) in beautiful Bamberg, Germany I flew a desk for the rest my career after graduating from Berkeley. I was a field engineer on the construction of the Army’s first “Amazon-style” storage and distribution center in Sacramento, CA, and I was serving in Germany when the Berlin Wall fell, as the Director of Public Works for Hohenfels Training Center (the largest Army base in Europe). Four years in Germany was followed by a Joint Duty tour in the Intelligence Directorate (J2), U.S. Strategic Command (Omaha, NE), the command that control the nation’s missile, bomber and submarine nuclear assets. With my desk underground beneath 40 feet of concrete, I never knew what the weather was like until I completed my shift.

In 1996 the Chief of Engineers, U.S. Army decided to send me home and I assumed command in July of the Detroit District. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Responsible for federal water resource development on Lakes Superior, Michigan, Huron and Erie with over 4,000 miles of U.S. shoreline, leading the District was a great job. There was never a dull day, as I learned on the first day, when I received a phone call from a New York City developer named Donald Trump, asking whether I had made a decision on his permit to open a floating casino on a “navigable water of the U.S.” outside Chicago. I signed the permit a few months later and received a nice personal invitation to a private pre-opening dinner (which I declined; the last thing the Army needed was a picture of me in uniform entering a casino).

I met my wife (Becky) when I was assigned to Sacramento in 1985, and we married in 1987. Our daughter was born in 1990 in Leavenworth, KS while I was attending Command & General Staff College, and our son was born while I was in command in Detroit. In April 1998 I received orders to attend the Army War College, but the Army made the mistake of telling Becky that after our year in Carlisle Barracks, PA I would be sent overseas for an “unaccompanied” tour, leaving her alone with a 9-year old and a 2-year old. Becky was not thrilled with raising a 2-year old alone, and I agreed to send out 4 resumes to test the civilian market – three resumes to generic job postings and one personal letter/resume to the CEO (Jim McNulty) of Parsons, an international engineering & construction firm headquartered in Pasadena, CA. Jim was a WestPoint graduate and retired Army officer, and I essentially explained the situation to him in my letter – do I stay in or get out? Within days he asked me to come out for an interview, which went well but I said I had to talk to Becky. I arrived home after the red-eye flight to find two dozen roses and a note to Becky – Jim had called her while I was still in Pasadena and worked out a deal, which sealed my fate.

We moved with our daughter and son to La Verne, CA where we lived for 13 years while I worked on various projects. In 2004 we won a large portion of the reconstruction effort in Iraq, and I deployed to the U.S. Embassy in Baghdad ( as a civilian) as the Deputy Program Manager for $4B in water and wastewater, part of the $18B Congress appropriated. When I first arrived, it was safe to go out for dinner on the economy, but during the summer security went to hell, with car and suicide bombings every day. With only the northern Kurdish areas offering relative safety, the Iraqi government’s plans for major new facilities or repairs in Shia or Sunni-controlled areas fell apart elsewhere. Plans for a new sewage treatment facility in Fallujah came to a halt that summer when Fallujah was occupied by virtually every insurgent group in Iraq, making visits impossible. A particular low point of my efforts in Iraq occurred when we successfully finished a sewage lift station in Baghdad and it was hit by a fuel-tanker suicide bomber the next day – killing no Americans but over 50 Iraqi civilians.

Between Iraq, I worked on major dam construction projects in Southern California for Parsons, including the $2B Eastside Reservoir (which involved 3 new dams) in San Bernardino County as a Project Manager, and the $416M San Vicente Dam Raise in San Diego County as the Construction Manager, where the existing 220-ft high concrete dam was raised an additional 117 ft. using Roller Compacted Concrete (RCC). In 2011 we moved to Ellicott City, MD where I continued my career with Parsons as the Program Manager for the design & construction of $4B in facilities for a government agency.

In 2014, I joined HDR, an international Architecture/Engineering firm headquartered in Omaha as their Director for Construction Services, Water. HDR is ranked No. 1 in bridge design (including the$4.4B new Tappan Zee Bridge, officially named the Governor Mario M. Cuomo Bridge) as well as the design of healthcare facilities (such as Huber River’s new 1.7-million-sf hospital in Toronto, that will be the largest acute care hospital in the greater Toronto area and the first in North America to automate all of its operational processes). My portfolio concentrates on much smaller water or wastewater projects for municipal clients across North America. At any given time, we have 60-70 projects under construction which results in a lot of travel for me, but also creates an environment where I am challenged everyday by amazing young professionals.

While still working, I admit to thinking about retiring eventually. Our daughter is a Registered Dietician in Settle, and our son is in law enforcement on the east coast so picking a retirement location could be a challenge – working allows be to put off that decision.

I passionately believe that the person I am is a result of being influenced and shaped by the people who surrounded me at various times in my life. I appreciate all my fraternity brothers who unknowingly contributed to my great life.

Thomas C. Haid

{Editor’s note – Fulda Gap was identified by Western strategists as a possible route for a Soviet invasion of the American occupation zone from the eastern sector occupied by the Soviet Union. The Gap represented the shortest route from the border between East Germany and West Germany to the Rhine River. Throughout the Cold War, North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and Warsaw Pact military forces remained heavily concentrated in the area. Constant patrols, surveillance, and alerts were carried out along the border, where opposing observation points stood less than 100 yards apart, until the reunification of Germany in 1990.

Brother Scott Kellman ’78 was Class President of the Michigan Student Body in his senior year, and he and Tom were both part of Michigamua; as a “secret society” it is not widely discussed! Their “Chief” that year was All-American football player (and all around good guy) Mike Kenn, who went on to a 17-year NFL career with the Atlanta Falcons, where he started in all 251 games that he played.}